Remember the game of darts?

Creating

thesis options for yourself is somewhat like the three chances in the game of

darts. Hopefully, one of them would hit the bull’s eye!

x

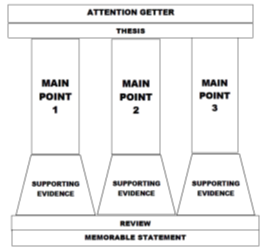

A good essay is pivoted in a centrally significant thesis.

But the road to a solid, defensible essay thesis is not always the quickest path between your thinking mind and the essay introduction in which the thesis resides.

You’ll recall that in the CSS Essay examination there are three types of topic formulations. Where the essay thesis is identified with the given topic itself, you have no option but to build upon that. But in situations where the topic is in phrasal form or is a question, after generating ideas and narrowing the scope of the topic, craft, not one but at least three claim statements. Then compare the three candidates and choose the one you would give the highest score in clarity as well as strength of opinion.